Sophie Kovel

A Long Duration of Losses

06.01.2023 — 11.03.2023

Paris

Materials: Exhibition text, Checklist

Press: Palm Pt. 1, Palm Pt. 2, Palm Pt. 3

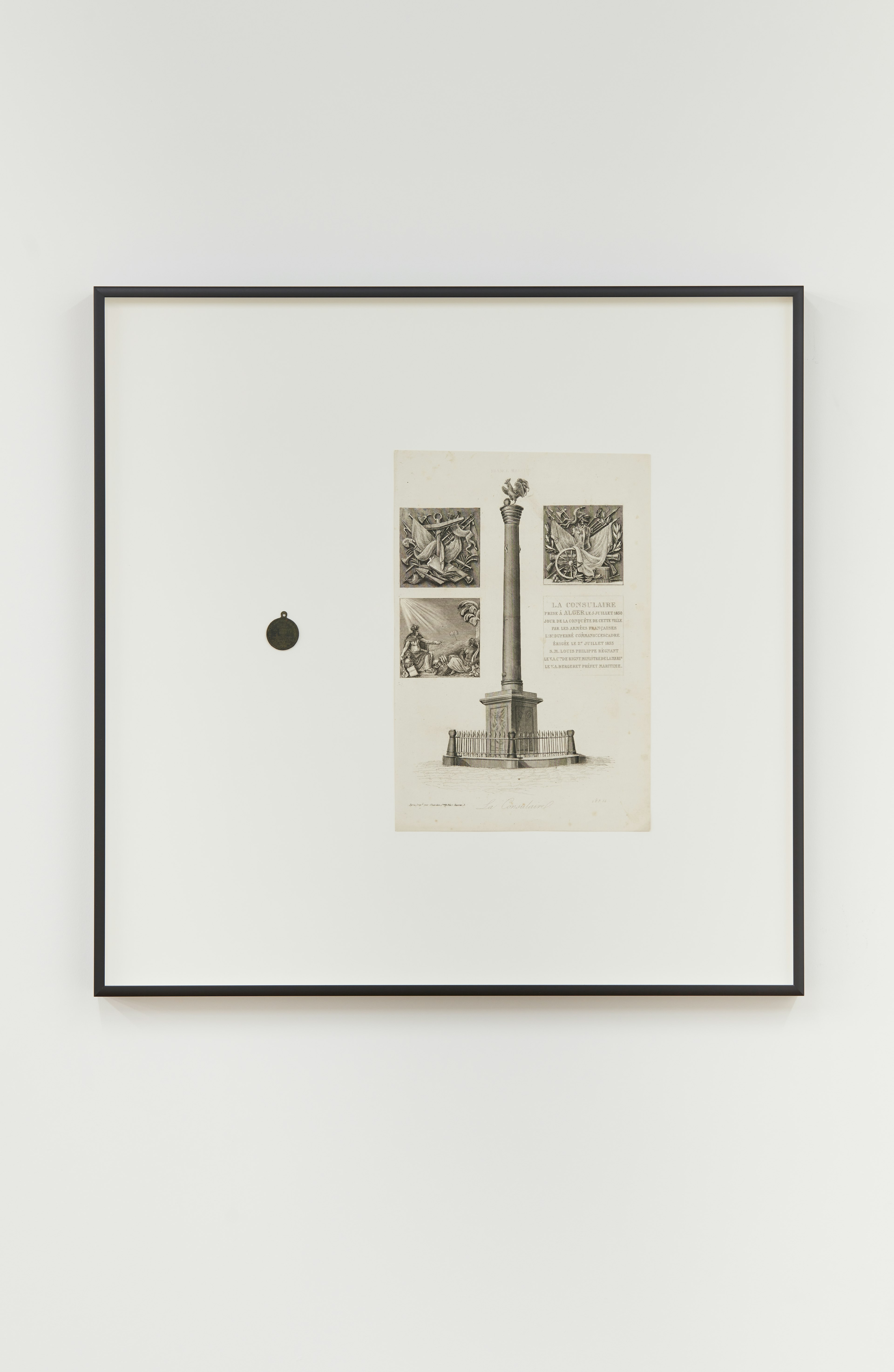

The first object that entered the Musée national de la Marine was a small replica of the Baba Merzoug, when it was an artillery cannon rather than an erected monument, before it was repurposed to commemorate the French war dead. It had, for centuries, protected the Bay of Algiers. In 1827, Charles X founded the Musée national de la marine. He would initiate the Invasion of Algiers three years later. It was then that the cannon was brought to Brest as a spoil of war.

***

Kateb Yacine wrote that the French language, too, is a spoil of war.

***

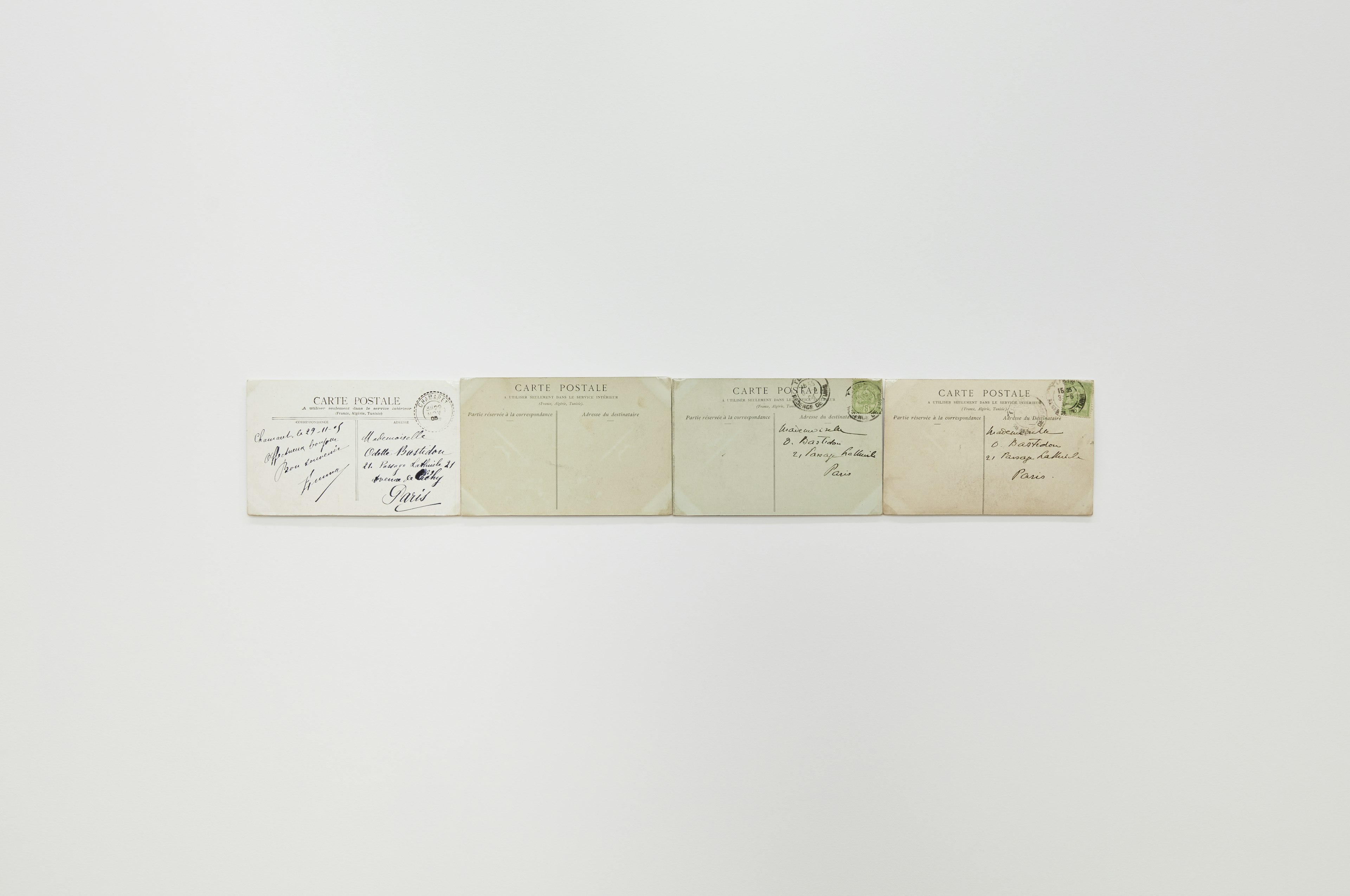

In 2017, a gift of postcards, wrapped in blue velvet, arrived from a San Francisco second-hand store. Two cards, both from Versailles: the Baths of Apollo and The Hall of Mirrors, with the colonial designation (in French): “For interior service only (France, Algeria, Tunisia).” That is, an interiority to the French empire. This was the recto-verso of French nationalism and colonialism.

***

Early in The Black Jacobins, C.L.R. James describes the confounded entwinement of economic “liberty” and forms of emancipation with slavery: “Long before 1789 the French bourgeoisie was the most powerful economic force in France, and the slave-trade and the colonies were the basis of its wealth and power. The slave-trade and slavery were the economic basis of the French Revolution. ‘Sad irony of human history,’ comments Jaurès. ‘The fortunes created at Bordeaux, at Nantes, by the slave-trade, gave to the bourgeoisie that pride which needed liberty and contributed to emancipation.’ Nantes was the center of the slave-trade. As early as 1666 108 ships went to the coast of Guinea and took on board 37,430 slaves, to a total value of more than 37 millions, giving the Nantes bourgeoisie 15 to 20 per cent on their money.”

***

It was at Versailles where the Code Noir was signed into existence. It is for this reason that Versailles is the beginning

***

Samia Henni notes that “it was not until 18 October 1999, also under the presidency of Chirac, that the French authorities approved the use of the official appellation La Guerre d’Algérie (‘the Algerian War,’ alternately translated as ‘the War for Algeria’) at French schools and in official terminology. Before 1999, the French government euphemistically called the unnamed and undeclared war Les opérations de maintien de l’ordre (‘enforcement of law and order’) or Les évènements d’Algérie (‘Algeria’s events’).”

***

Zoe Leonard’s views of Niagra Falls describe a tourism of another kind of national fantasy, through the eyes of repetition and accumulation. A reading of the formalism of tourism, and grandeur—if sublimity—of the North American landscape. What happens when projections of national landscape omits its colonial territory? The colonial territory, unpictured.

***

The colonial continuum: unpictured. This is one small attempt at such a picturing, hung at the height of the state’s barrier enclosing, commanding ownership of a spoil, in Brest.

***

“Great monuments are raised up like dams,” Bataille wrote in 1929, “pitting the logic of majesty and authority against all the shady elements: it is in the form of cathedrals and palaces that Church and State speak and impose silence on the multitudes.”

***

“For Bataille,” Bhakti Shringarpure writes, "the storming of the Bastille reflected the animosity people felt towards the monuments that had become their masters. He illustrates that the human order is bound up in the architectural order.” She continues, “Thinking about architecture through this lens dramatically alters the easy presumption that monuments are the souls of societies or metaphors of progress or symbols of national pride but show that they also have the ability to command, prohibit, exclude and dominate.”

***

“Ideologies enacted through colonialism,” Léopold Lambert echoes, “systematically linked to slavery—or imperialism requires not only architecture to implement themselves, but also material symbol to provide a dominant narrative.’”

***

“By taking over the signs and language of officialdom,” Achille Mmembe writes, “people have been able to remythologize their own conceptual universe [...] The process is fundamentally magical: though it may demystify the commandement or even erode its supposed legitimacy, it does not do violence to the commandement’s material base. At its best, it creates pockets of indiscipline on which the commandement may stub its toe, though otherwise it glides unperturbed over them.” Empire, displaced from its claw. In the time that follows, a penned or patinated object, against such semblances, and for far more than aching feet.

– Sophie Kovel

Paris, January 2023

Sophie Kovel is an artist and writer. Recent exhibitions include Jenkins Johnson Gallery, New York (2022); University of California, Los Angeles (2022); the Jewish Museum, New York (2022); VERY Project Space, Berlin (2021); and Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen (2021). Kovel has spoken on panels and symposiums at universities and institutions including Columbia University and the Brooklyn Public Library. Her interviews and criticism have been published in Artforum, BOMB, Frieze, Spike, and elsewhere. Kovel is a recent graduate from Columbia University’s MFA in New Genres, where she was awarded the Agnes Martin and Andrew Fisher Fellowships, and is a 2022–2023 studio fellow in the Whitney Independent Study Program.

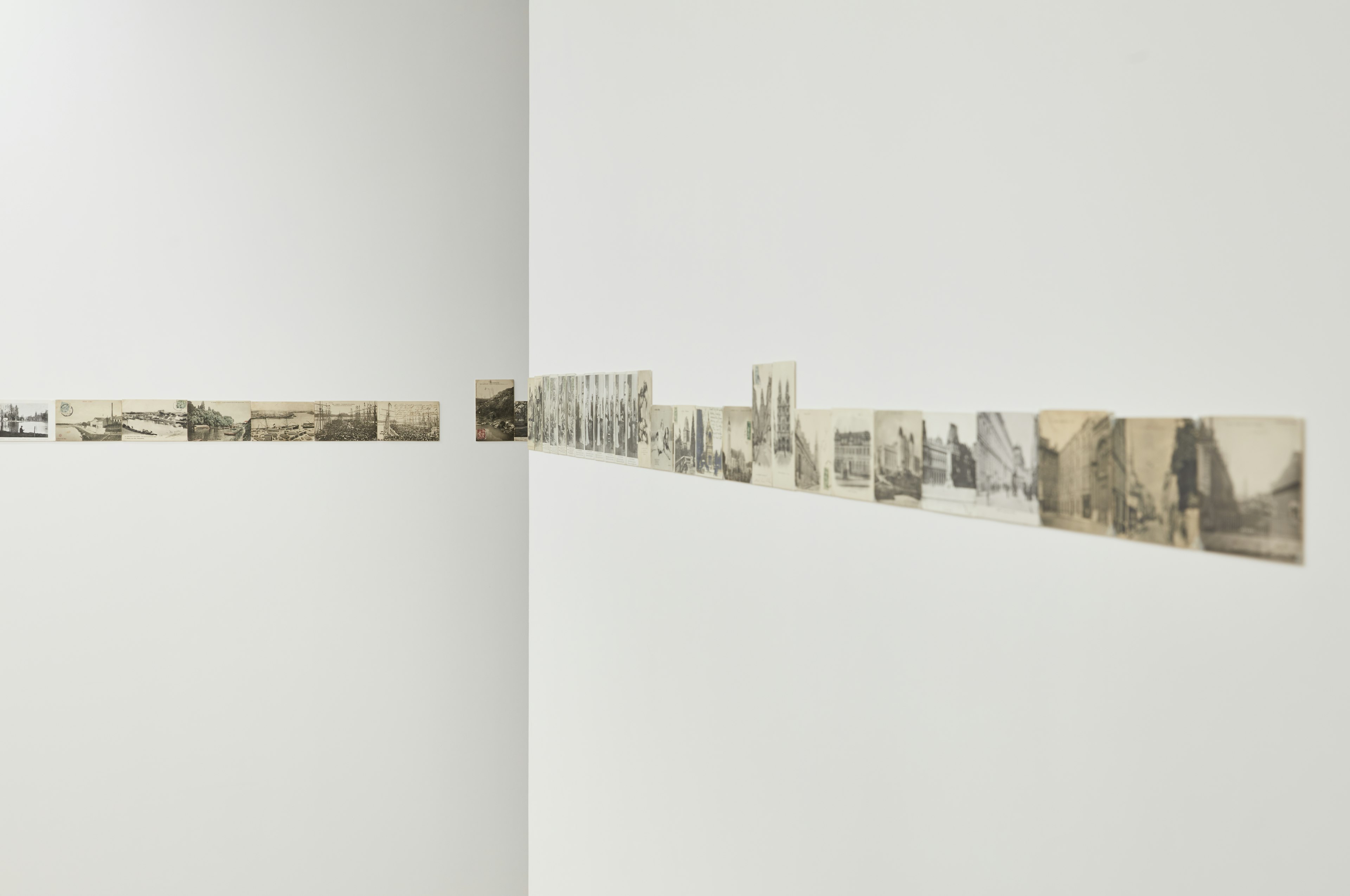

Sophie Kovel

Lieu de mémoire (À utiliser dans service intérieur), 2017-2022

67 French colonial postcards (circa 1904–10); hung at the height of the surrounding fence at La Consulaire, Brest

dimensions variable

Sophie Kovel

Lieu de mémoire (Coq en bronze), 2022

polyurethane, patinated copper

38.1 x 25.4 cm

Sophie Kovel

A Long Duration of Losses (Baba Merzoug) I, 2023

framed engravings

50 x 50 cm

Sophie Kovel

A Long Duration of Losses (Baba Merzoug) II, 2023

framed engravings

50 x 50 cm

Sophie Kovel

A Long Duration of Losses (Baba Merzoug) III, 2023

framed engravings

50 x 50 cm

Sophie Kovel

A Long Duration of Losses (Baba Merzoug) VI, 2023

framed engravings

50 x 50 cm

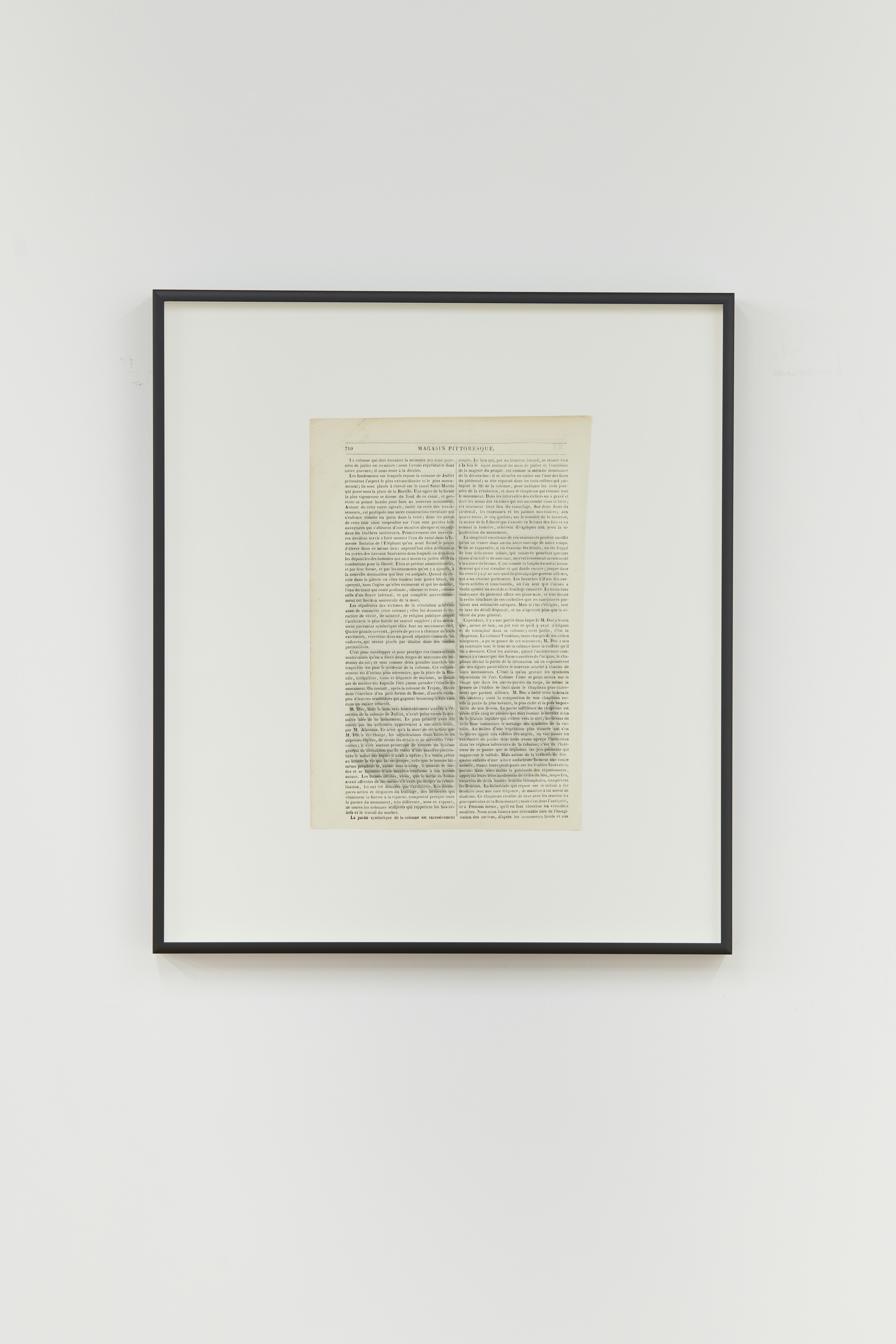

Sophie Kovel

A Long Duration of Losses (Le Magasin Pittoresque) I, 2023

framed engravings

45 x 40 cm